The Uncharted series finally asks the question, “what if Lego Indiana Jones happened with real people?” You follow treasure hunter Nathan Drake as he gallivants around the world uncovering hidden treasures in an effort to discover secrets of the past and prevent them from falling into the wrong hands.

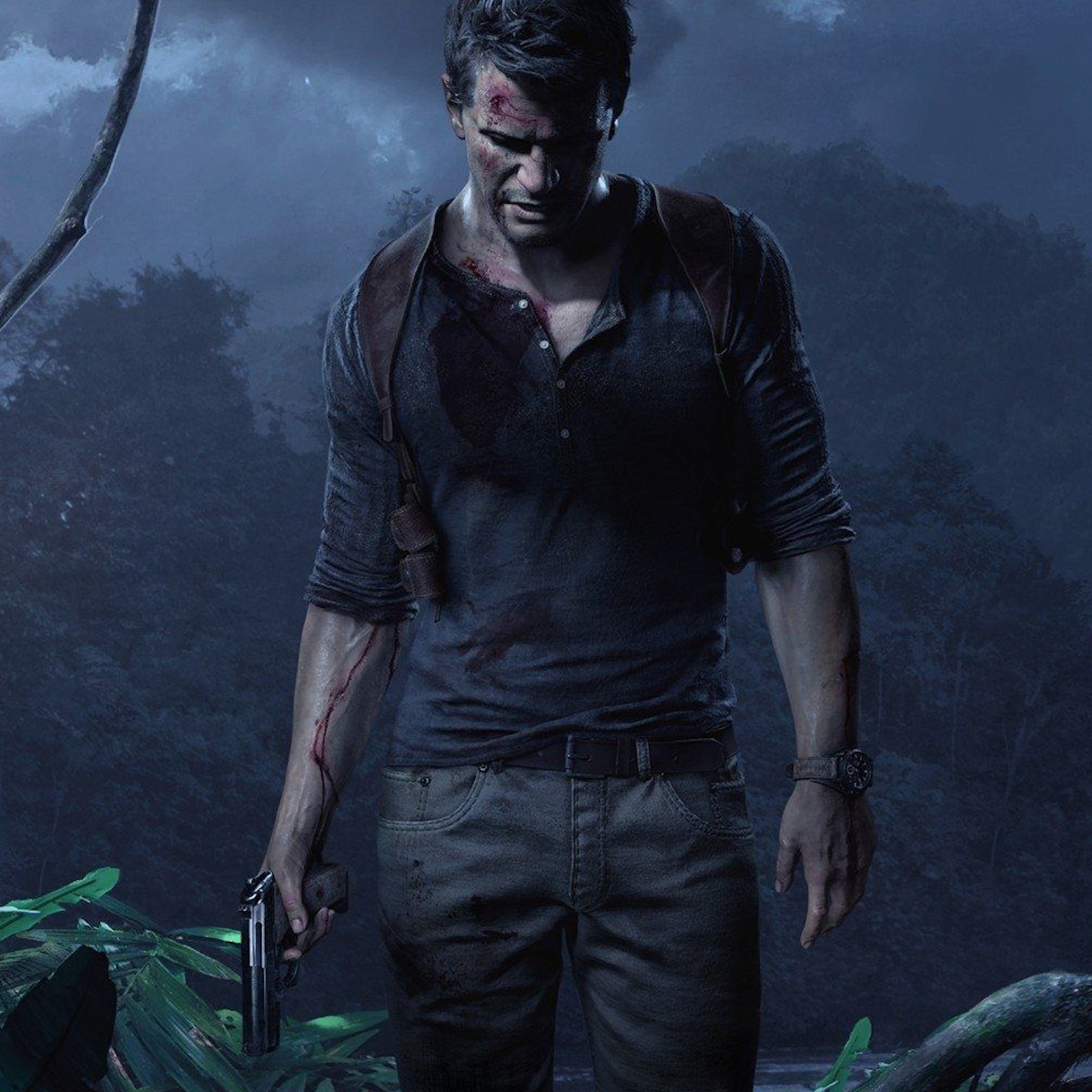

Along with a rotating cast of characters you’ll traverse sprawling ruins, jungles, and cities engaging in fire fights and death defying leaps such as scaling the side of a cliff or hanging for dear life from a plane. These games are theatrical, narrative driven stories that use lush environments as a backdrop to convey the thrilling adventures of a man that walks the thin line between greatness and failure, which is the strongest aspect of these games. The characterization and story.

These characters aren’t just some generic action squad with their personalities reflecting their team role. Rather, most of these characters are deeply flawed, playing off one another in light of the danger they face. Drake is this arrogant ass half the time that struggles to balance his desire to solve the mystery with his personal issues, especially with his romantic interest Elena. Often times he throws caution to the wind, using the looming threat of villainy as justification for his own selfish needs to find the treasure. He continually puts himself and others at risk, choosing to ignore the blatant warning signs that drag him into these harrowing messes.

Elena develops into the voice of reason for Drake as their romantic involvement increases. She starts out as this naïve journalist that gets overwhelmed as the world around her descends into chaos. Eventually she evolves into a highly capable adventurer that saves Drake from himself and the psychotic murderers that want him dead. Sully is the father figure that Nate desperately seeks in life, going along with the plan but showing a cautious, yet light-heartened attitude the entire time. Sully, likewise, sees Nathan as the son he never had, and while he loves the call of adventure, with Nathan he wants to help him avoid the mistakes he’s made and attain the life he’s never had. Chloe is this only-out-for-herself type that wants to avoid the greater responsibility of preventing the villain from unleashing destruction and focuses on getting the treasure, but will still answer the call for help despite her initial hesitations. Sam, Nate’s brother that doesn’t show up until the 4th and final game, A Thief’s End, embodies the idealistic role-model Drake looked up to as a child, but whose desire to find treasure in order to prove something drives him and Nate down a host of poor decisions.

Where most videogames would insert some generic schtick that represents the player as a stand in, Uncharted simply lets you come along for the ride. These games are less about reaching the destination and more about the journey along the way since the story is about the character’s relationships. Those relationships aren’t just explored in the cinematic cut scenes, Drake and his companions will parkour up mountains, through warehouses, or down ravines and actually talk to each other. You’ll boost Sully up a cliff and comment on “what a great ass he has,” you’ll have Chloe ask if that’s a Tibetan artifact in your pocket or if you’re just happy to see her, you’ll have Elena joke and chide Nathan in the same breath for not thinking through his plan, and you’ll have Sam correct his little brother when he gets the wrong pirate sigil mixed up. Instead of just interspacing character building cut scenes, the game will use these in-between moments to really build each relationship to Drake while showing how these individuals operate as people. They will make light of the problem, but allow enough time for the gravity of that situation to settle before shifting the tone, and that’s exactly what I want out of a narrative driven game. Unlike Call of Duty or other shooter campaigns where the NPC’s will just guide the player to the next checkpoint, the character’s in Uncharted have a wit and charm to them that urges the player to continue onward.

Gameplay wise, these games can pretty much be separated into two categories. Shootouts and “platforming.” I put “platforming” in quotes because it’s not really platforming. Timing is rarely a consideration and these sections of the game you can’t really lose. Typically, you’ll climb or traverse some environment by holding the analog stick in the right direction and sometimes pressing x to jump across a ledge. It’s about just navigating a path rather than actual platforming found in the likes of Naughty Dog’s Crash Bandicoot series. These sections of the game can get stale fast, even with the enjoyable dialogue, because it just goes on for several minutes without any challenge. Typically, most shooter-adventure games will have multiple areas that you walk between as you mow down enemy forces, but in Uncharted those short in-between area moments are replaced by these long climbing sessions. They’re just like quicktime events except slow as hell and I don’t ever want to do them again. These long periods of downtime as you simply wait until it’s over, and you reach the next part, can really bog down the games pacing. They make up a surprising amount of gameplay, and while beautiful at times when you’re scaling a mountain and look out at the gorgeous island landscape before you, it can be cumbersome as you’re trying to get back into the action.

These games are theatrical, which is both a good and bad thing. It’s good because it lends a real sense of urgency and weight to what you’re doing. Outrunning a falling tower or enemy vehicle barreling down the alleyway or making that desperate leap off a collapsing bridge really does create for exciting moments. Uncharted 2: Among Thieves starts you out in a train car suspended from a snowy cliff that you carefully maneuver out of all while suffering from a gun shot wound. Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception has you chase down a plane and then suspends you by a cargo net from said plane while you’re being shot at. These scenes lend a huge sense of legitimacy to what you’re doing and deliver on that promise of thrilling adventure. Where this starts to work against the game comes from navigating some of these moments. You’ll get the shittiest camera angles showing a collapsing tower, speeding boulder, or torrential water coming towards you, but it blocks what’s in front of you. The controls can feel clunky as you try to avoid obstacles or jump over a gap that instantly appears. The bridge in Uncharted 2 at the end as you escape the city and the burning Chateau and sinking ship in Uncharted 3 are the most blatant examples of this. It’s not hard, just slightly annoying as you awkwardly meamble through, and it distracts from the cinematic scene it creates. During the “platforming” sections you’ll also be barraged with close calls as you jump to a pipe that almost snaps or a rock hold that will break as Drake catches himself on another ridge to prevent his plummet.

One moment is fine, but when every other questionable gap is treated this way it loses all dramatic tension. Every time Drake makes what looks like a little too risky of a jump he’ll flounder for a moment before pulling himself up to safety. Like I said, these sections can go on for a while to the point that you just want to get through them as quickly as possible, but after having to watch these close call animations slow you down can get weary. These games aren’t that long. The first three are all 7 – 10 hours, with Uncharted 4 coming in close to 12-15 hours, but as I became more invested in the story I just wanted to get to the action. I highly recommend you play these games on the PS4 where the graphics have been improved, and that adds to the overall experience. Uncharted 4, especially with its longer length, introduced more of the platforming sections, but with how crisp the graphics are I found them more enjoyable as the theatrical elements were brought to life.

The grappling hook and sliding sections also livened up the “platforming.” They also create these moments that just feel badass. You’ll fly down a slide or repel from the hook, launching Drake into the air as he clocks a dude. Nathan descends on his victims, pile driving them into the ground like Stone Cold Steve Austin from the ropes. Or, you’ll fly down and avoid gun fire as you make a narrow escape. It creates more cinematic scenes, but I still think the “platforming” sections could be streamlined. Instead of introducing more climbing, inclusion of another fire fight here or there would keep the player more engaged.

The combat provides a solid shooter. There were times, especially in Uncharted 3, where I would encounter a glitch and not be able to pick up a weapon or ammo an enemy had dropped, but the core gameplay still held up to the end. Uncharted 4 really improved upon the combat with the addition of the grappling hook and by leaning into the stealth aspects. In the first three games, there are stealth elements to fights, but the games only embrace them on the surface. Typically, they push the player into a shootout rather than a Metal Gear Solid type of skirmish where you strategically take out unsuspecting enemies. In Uncharted 4, they give the player tall grass as coverage and enemy sensors to indicate detection. In those moments, the “platforming” and combat come into perfect harmony as you hang from the side of the ridge to avoid detection and take out a guard before jumping to the next hold or diving into the grass to silence another. It breathed new life into the combat, while sticking to its roots. Meanwhile, the grappling hook adds a new element to the firefights as you swing in the air trying to avoid a hail storm of bullets.

Uncharted 4, in particular, ended up being my favorite just for the story alone. The hunt for Henry Avery’s treasure coupled with the more mature and gritty take plays out just like a movie, and graphically it delivers a show. Chapter 17 has this beautiful moment after Elena ends up saving Nate. You have to go through this elongated driving and “platforming” section that are used to artificially lengthen the campaign, but this time it actually delivers something important. Nathen has lied to his wife, Elena, for a majority of the game and once she rescues him after he falls off a cliff she expresses the doubt in continuing their relationship. She says, “I almost didn’t come back this time,” and for the next twenty minutes it becomes a dating simulator in the best way possible. As you drive across the jungle you can feel Nate looking for forgiveness and Elena struggling to forgive. There is genuine, uncomfortable silence as you understand Nathen is just searching for the right words. He cracks a few jokes here and there, just trying to lighten the mood, and Elena laughs or makes her own retort, but the somber reality of Nate’s betrayal still looms in the air. At one point, you ride an elevator after having this discombobulating conversation with Nathan attempting to say, “I’m sorry.” He asks Elena why she came back, and her response is about their wedding vows of “for better or for worse.” You feel the emotional weight of a woman that is tired. Of the worn trust. Of the hurt she feels, and after you both climb in the car and drive in silence through this scenic landscape with a melancholic piano playing softly in the background you understand both characters completely as they work to reconcile and move past Nate’s mistake. It’s a heavy moment and one of the best story telling elements across all four games.

And it’s those moments of the game where it shines the brightest, a poignant testament to what Naughty Dog has worked towards all these years, emotional investment. While these games are flawed, those immense plot points keep you constantly engaged throughout the entire run time, and I think they’re must plays for anyone that owns a PlayStation. The sense of wonder and adventure are delivered in a fairly concise and well thought out narrative that gives the players the complete experience of finally getting to live out Lego Indiana Jones.